Here’s something that kept me thinking: A student scored 85% in Engineering Mathematics. Could solve differential equations in his sleep. Then, we gave him a simple case: estimate how many EV charging stations Hyderabad needs by 2030. He stared at the problem for ten minutes. Then asked, “What’s the formula?” There is no formula. Only thinking. And that’s when I realized: we’re graduating engineering students who’ve mastered mathematics but lost mathematical thinking.

For the past few years, we’ve been building something we call the 7AI framework that tracks students across seven dimensions: Aptitude, Knowledge, Personality, Technical skills, Social consciousness, Application skills, and Career fitment.

The idea was simple: stop looking at just exam scores. Understand the complete picture of a student’s learning identity.

We tracked behavioral data: Micro-assessments, project performance, how students approached problems, where they got stuck, what made them give up, and what made them persist.

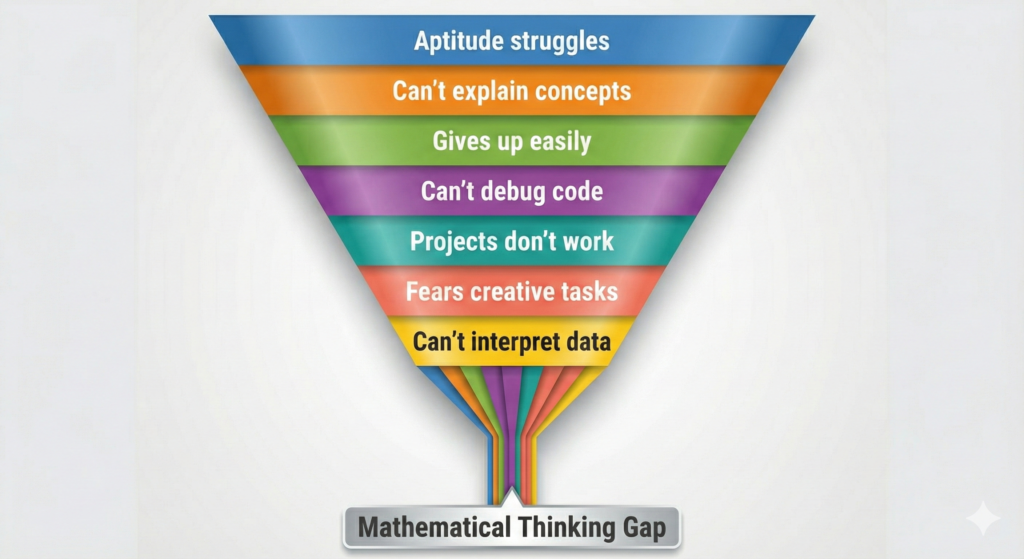

And then something strange started happening. Surprisingly, we kept finding the same answer underneath completely different problems. A student bombs aptitude tests despite good grades? We’d dig into their data and find the same root cause. A different student writes perfect code but can’t debug? Different dimension, different skill. But the underlying gap? Same thing. Another student whose projects never quite work; another who freezes during creative assignments, and yet another who can ace exams but can’t explain concepts.

Different students; different struggles; different dimensions, yet the same missing foundation.

And on National Mathematics Day, I finally have the language to explain what we’ve been seeing: it’s mathematical thinking. Not mathematics. Mathematical thinking.

Let me show you what our data revealed.

The Aptitude Mystery

First place we noticed it: aptitude assessments. We had students with good grades who consistently bombed logical reasoning tests during placements. They’d get frustrated: “I’m just not good at aptitude.” So we dug into their 7AI profiles. Watched where they got stuck.

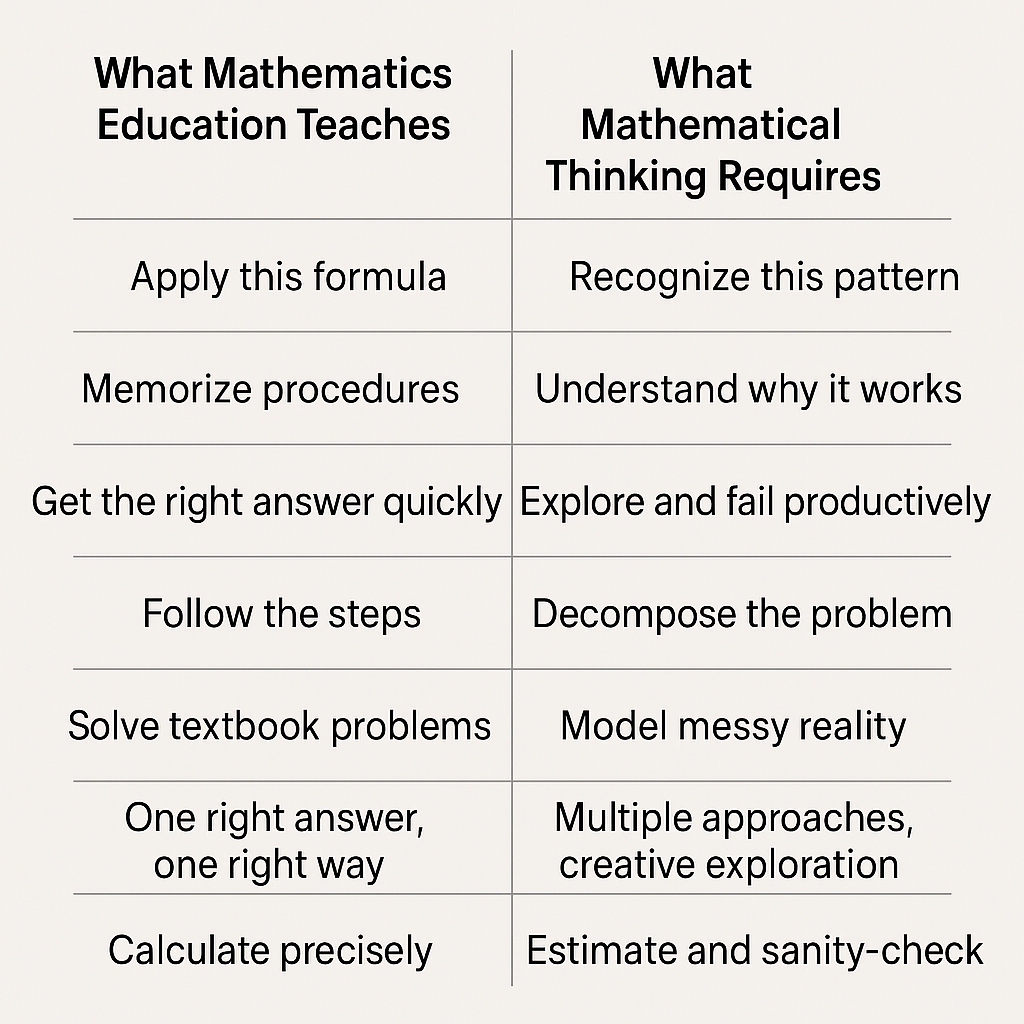

They weren’t struggling with aptitude; they were struggling with pattern recognition. Those logical reasoning questions? Just patterns. Find the next number. Identify which shape doesn’t belong. Spot the relationship. But these students couldn’t see patterns. They were looking for formulas. Procedures. Rules to apply. Because that’s what we taught them mathematics was: a set of procedures to memorize and execute.

Ramanujan saw patterns others couldn’t. Our students? They’d reach for a calculator. The World Economic Forum calls this ‘analytical thinking’, their number one skill for 2025.

First clue: When students struggle with aptitude, the root cause is often weak pattern recognition. A mathematical thinking skill we never explicitly taught.

The Understanding Gap

Next dimension: academic performance. We had high performers who couldn’t explain what they’d learned. Ask them to explain Fourier transforms. “It converts time-domain signals to the frequency domain.” “Right, but why? When would you use it?” Silence.

They’d mastered procedures without understanding concepts. Solving textbook problems? Easy. Explaining why? Impossible. Real understanding means explaining it, simply seeing why it works, not just that it works.

Ramanujan would write to Hardy saying “I believe this formula works because…” He could explain his intuitions, make connections, show relationships. Our students were executing algorithms without comprehension. OECD calls this ‘mathematical literacy’—understanding context, not just computation.

Second clue: High grades without deep understanding equals procedures learned without mathematical reasoning.

The Persistence Problem

Third dimension: personality. Students would attempt a problem, get it wrong, and never try again. We initially thought: fear of failure. But these same students persisted in other contexts—debugging code, perfecting presentations. So, what was different about mathematical problems? The answer: we’d taught them that math has right answers and wrong answers. We never taught them that mathematics is exploration.

Ramanujan filled notebooks with failed approaches. Mathematical thinking includes tolerance for ambiguity. Our students didn’t have that. We graded them on first attempts, rewarding speed over exploration

Third clue: Low persistence on problem-solving tasks often stems from never learning that wrong answers are part of mathematical exploration.

The Debugging Paradox

Fourth dimension: coding skills. Students who wrote complex code fell apart when debugging. They’d stare at error messages, try random fixes, and Google desperately. Their coding skills were fine; their logical decomposition skills were missing

Fourth clue: Weak debugging skills often reflect weak logical decomposition.

The Translation Problem

Fifth dimension: skill application. Projects failed at implementation. “Why this motor?” “The tutorial used it.” “Did you calculate if it’s powerful enough?” “I didn’t know I was supposed to.” They couldn’t model real-world problems mathematically.

Engineering is full of estimation moments: Is this beam thick enough? Will this battery last long enough? Can this server handle the traffic? Those aren’t textbook problems with given formulas. They’re messy realities that you have to turn into something you can reason about.

Ramanujan looked at real mathematical questions and built frameworks to explore them. Our students were waiting for someone to hand them the framework.

Fifth clue: Inability to apply skills practically often stems from never learning to model real-world problems mathematically.

The Creativity Freeze

Sixth dimension: creativity. “Design a solution to reduce food waste.” Panic. “What’s the right answer?” They were terrified of uncertainty, not incapable of creativity. Years of mathematics education taught them: one right answer, one right way. Exploration is wasteful. Stick to the formula.

Ramanujan’s famous 1729 discovery came from playing with patterns. “What numbers can be expressed as sums of cubes in multiple ways?” That’s creative mathematical exploration. Our students couldn’t do that. We’d trained the exploration out of them. NEP 2020 emphasizes this exact gap: applying knowledge in real-world contexts.

Sixth clue: Inability to think creatively often traces back to mathematics education that punished exploration and rewarded rigid procedure-following.

The Decision-Making Gap

Seventh dimension: career readiness. Students struggled with data-driven decisions. “Should we add this feature?” “I think users would like it.” “What does the data say?” “I don’t know how to interpret data.” This student solved differential equations but couldn’t read a graph.

Every engineering career requires quantitative reasoning under uncertainty. Not complex math. Just the ability to look at numbers and spot trends. Estimate and sanity-check. Make judgments with incomplete information. That’s mathematical thinking in the real world.

Seventh clue: Poor career readiness often reflects an inability to make quantitative decisions. Global employers consistently rank quantitative reasoning in their top three required skills.

The Pattern Emerges

Seven dimensions, seven struggles, seven places where students hit walls, yet one underlying cause: missing mathematical thinking.

Not missing mathematics knowledge. They had the knowledge and could pass the exams. They were missing pattern recognition, conceptual understanding, tolerance for exploration, logical decomposition, real-world modeling, creative reasoning, and quantitative decision-making. All mathematical thinking is absent from their education.

On December 22nd, we celebrate Ramanujan. Can we also celebrate what he taught us? Learning mathematical thinking, not just procedures, pattern recognition, relentless exploration, and reasoning through uncertainty. Not just the ability to solve for x.

So this Math Day, let us think of “How do we stop destroying the mathematical thinking that every student starts with?” Because they all had it once. Every child who asks “why?” and “what if?” has mathematical thinking. We trained it out of them: Curiosity became procedures; Exploration became formulas; Thinking became calculating.

The 7AI framework revealed what was hiding in plain sight: you can’t build great engineers without mathematical thinking. And you can’t build mathematical thinking with the way we currently teach mathematics. That’s the pattern in our data. That’s the answer we kept finding.