Every year, thousands of Indian families gather around dining tables to make a calculation that will shape their children’s futures. The equation is complex: tuition fees in lakhs, potential earnings in dollars, visa uncertainties, and years away from home. For many, the answer has consistently pointed abroad. But when that calculation suddenly shifts, what happens to the students, and more importantly, are Indian institutions ready to offer them a genuine alternative?

When immigration policies tighten in traditional study destinations, it’s rarely a permanent change. Political winds shift, economic needs evolve, and borders that close eventually reopen. But the real question isn’t about policy cycles. It’s about what happens to the students caught in between, and whether their home countries are ready to receive them.

India currently sends over 1.3 million students abroad annually, with 465,000 choosing the United States alone. That represents a $40+ billion annual outflow in tuition and living expenses. Recent policy shifts (from dramatic H-1B visa fee increases to proposed enrollment caps at top universities) are prompting a fundamental reassessment of this exodus. The question isn’t whether these specific policies will last, but whether Indian higher education can finally build institutions worthy of the talent it’s been exporting for decades.

The Quality Paradox: Why Students Leave

The uncomfortable truth is that Indian students don’t leave solely for better job prospects. They leave because of a persistent quality gap that no amount of nationalist sentiment can wish away.

India invests approximately 0.65% of its GDP in research and development, compared to China’s 2.43% and developed nations’ spending over 2%. This translates directly into what students experience: outdated labs, limited research opportunities, and faculty stretched impossibly thin across massive student populations.

While India’s top five universities have improved their rankings, this masks a deeper issue: beyond a handful of IITs and IIMs, whose acceptance rates are less than 2%, the system remains starved of resources and autonomy. Curricula lag industry needs by years, bureaucratic regulations stifle innovation, and the best Indian academics often teach abroad, where research infrastructure and compensation match their ambitions.

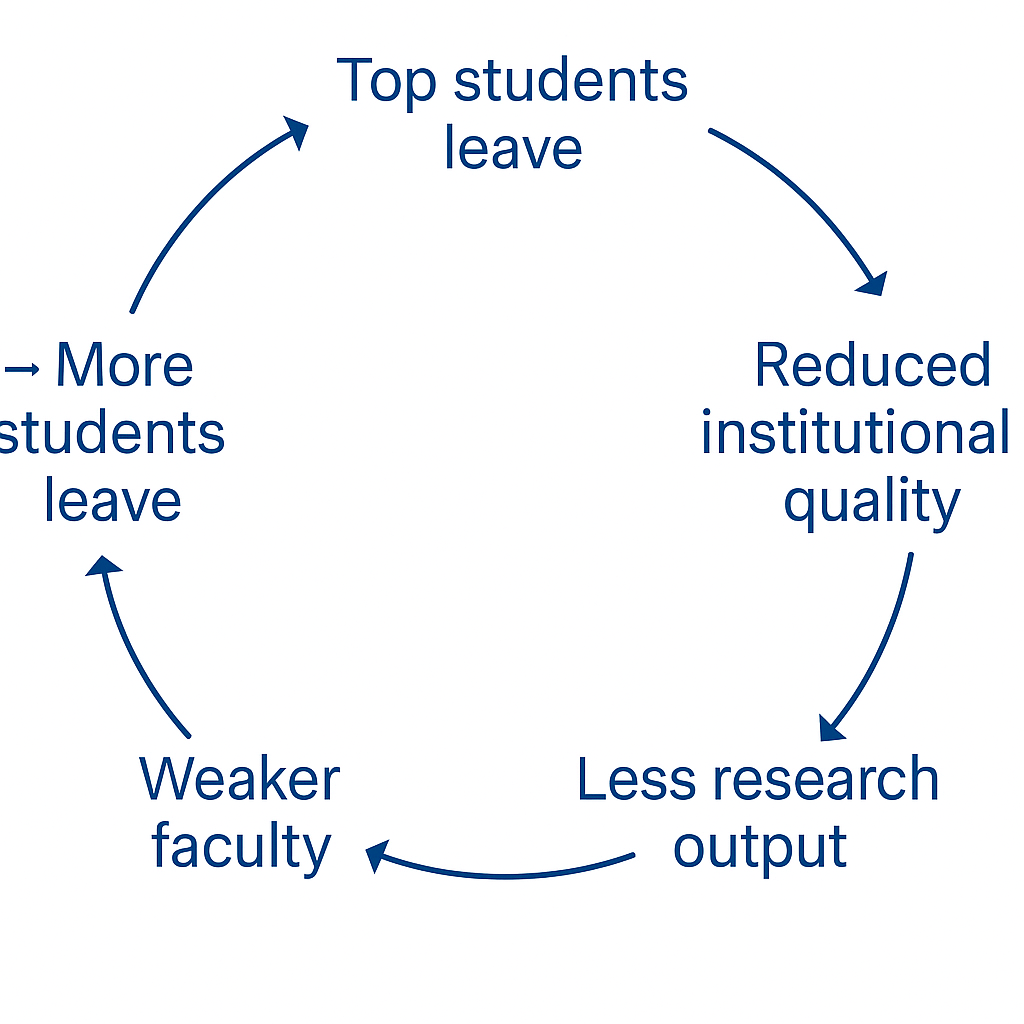

The result is a self-perpetuating cycle: top students leave, which reduces institutional quality, which drives more students to leave. International rankings aren’t just vanity metrics. They reflect research output, faculty quality, and industry collaboration that directly impact student learning.

The New Mathematics of Staying

When visa policies become uncertain and expensive, students naturally recalculate their options. Facing $100,000 in H-1B visa fees, possible enrollment limits at top universities, and years of immigration unpredictability, many are questioning whether studying abroad still makes financial sense.

This isn’t about any specific policy; those will change. It’s about uncertainty itself becoming part of the decision. Students and families value knowing what to expect, and when that clarity disappears, they consider other paths.

The numbers tell an interesting story. If even 20 to 30% of students who would have gone abroad choose to stay in India, billions of dollars remain in the domestic economy, creating real demand for quality education here. But there’s an important condition: this only becomes valuable if Indian universities can effectively teach and prepare these students. Without that, we simply move the problem from students leaving to students staying in institutions that don’t adequately serve them.

The Adaptation Imperative

Indian higher education institutions face a stark choice: treat this moment as a temporary windfall of captive students, or use it as a catalyst for fundamental transformation. The difference will determine whether India becomes a knowledge economy or remains a source of talent for others.

- Curriculum and Relevance: While the National Education Policy 2020 has catalyzed important changes, including industry partnerships and embedded certifications at several universities, implementation remains uneven. The challenge is scaling these best practices across thousands of institutions. Universities that have adopted semester-wise curriculum reviews with industry advisory boards show better graduate outcomes. The goal should be making these innovations the norm rather than the exception, ensuring every student benefits from current, practical learning regardless of which institution they attend.

- Research Infrastructure: Without substantial investment in labs, libraries, and computational resources, Indian institutions will remain teaching-focused rather than research-intensive. This requires both government funding and private sector partnerships that bring real R&D work onto campuses. Research parks adjacent to universities, joint faculty appointments with industry, and sponsored research chairs can bridge this gap.

- Faculty Quality and Autonomy: India needs to reverse its academic brain drain. This means competitive global compensation, research sabbaticals, and genuine academic freedom. Universities must have autonomy in hiring, admissions, and program design (the regulatory straitjacket that treats all institutions identically must loosen for elite institutions to emerge).

- Global Standards, Local Context: The goal shouldn’t be just retaining Indian students but attracting international students. This requires instruction that matches global standards, international accreditation, and dual degree programs with top foreign universities. Countries like Singapore and South Korea offer instructive examples. Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and the National University of Singapore (NUS) reached top global rankings within four decades of their founding, while Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) became a world-class institution in about five decades, all through sustained government investment, institutional autonomy, and clear focus on research excellence.

From Necessity to Destination

The ultimate measure of success won’t be how many students stay because they have no choice, but how many would choose Indian institutions even if all borders were open.

While frameworks like Outcome-Based Education have been adopted since India joined the Washington Accord in 2014, the gap lies in consistent execution. Many institutions have the structure but struggle with genuine implementation. Similarly, recent government commitments like the Rs 20,000 crore research allocation in Budget 2025-26 signal positive intent, but translating budget lines into world-class research output requires institutional capacity that takes time to build.

India has the fundamental ingredients: talented students, economic growth, and increasing policy attention to education and research. The challenge is converting these inputs into tangible outcomes. This means universities must track and transparently report not just graduation rates but actual career outcomes, research publications, and industry impact. Empowering students with analytics that reveal their learning strengths and gaps can transform passive education into personalized, outcome-driven learning experiences.

The 2035 Vision

Immigration policies will continue their cyclical nature. Countries that need talent will eventually open doors; those that close them will face economic consequences. But Indian higher education cannot afford to wait for the next cycle.

The opportunity before Indian institutions isn’t about capitalizing on someone else’s restrictive policies. It’s about building quality that makes the destination question irrelevant. Success will look like this: at least one Indian university consistently ranking in the global top 50, India hosting 100,000+ international students annually from diverse countries, and Indian university research being cited and built upon by scholars worldwide. When these milestones become reality, when Indian graduates are sought after globally not despite their education but because of it, that’s when India will have truly arrived as an education hub.

The students staying home today because of visa uncertainty deserve institutions that challenge and prepare them for a global future. Whether Indian higher education rises to meet them will determine not just individual careers, but India’s trajectory as a knowledge economy for decades to come. The choice isn’t between brain drain and brain gain (it’s between mediocrity and excellence). And unlike immigration policy, that choice is entirely ours to make.